By Anna Goodman, Staff Writer

Almost half of children have some level of fear of the dark, and yet when we’re older, we’re inexplicably drawn to it. “Evil tends to fascinate us, you know…we want to know what drives someone to do these evil, unthinkable acts because it’s so outside of our own realm—for most of us,” Stacey Nye, a psychology professor told Milwaukee’s NPR in their article “The Double-Edged Sword of True Crime Popularity.” The article goes on to say that, often due to their higher likelihood of being the victims of crime and the genre’s necessary discussions on safety and mental illness, the vast majority of true crime viewers are women who struggle with their own mental health.

And I’m one of them; I began listening to the true crime podcast “Fresh Hell” in late 2020, due to my interest in a specific case, and have been excited to check my phone every Friday afternoon since then. On the surface, it looks like every other true crime podcast: it’s hosted by two white, female friends in their 40’s who have an interest in the genre and wanted to talk about it.

But it’s not just crime; Fresh Hell has many episodes discussing interesting supernatural phenomena, dark history, and famous disappearances, and places an emphasis on mental health. As the tagline states: they cover “murder, mystery, and the macabre throughout history”. And the hosts, Annie and Johanna, after nearly half a decade of podcasting and over two hundred episodes, have never met in person; the former lives in Boston and the latter in Austria.

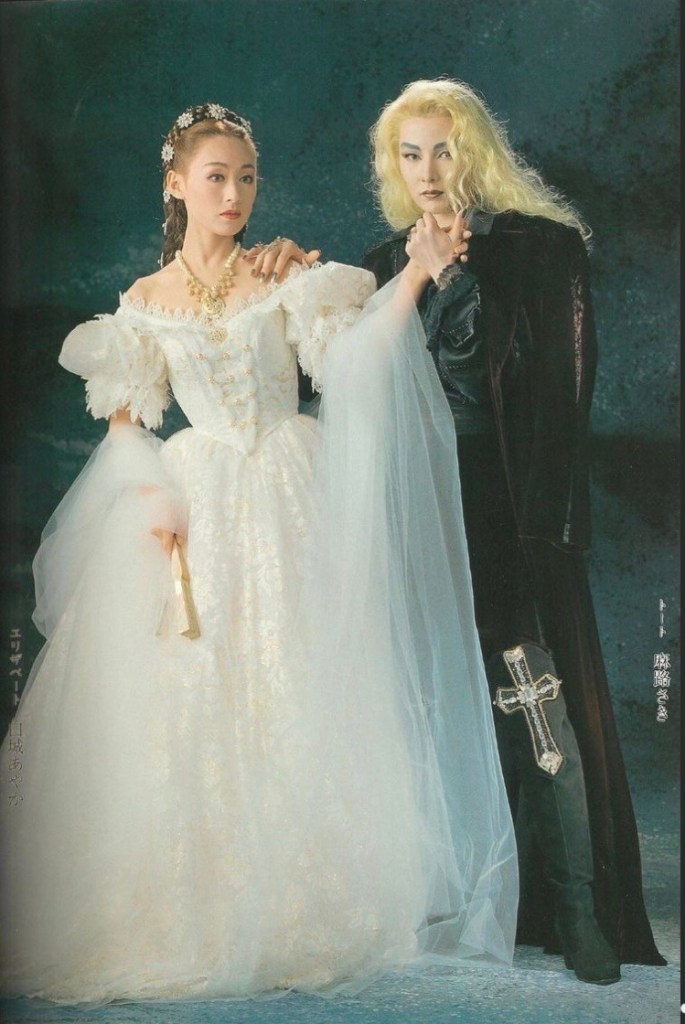

At the end of each episode, the hosts choose “something good” from their week, to lighten the mood and remind their listeners that all is not doom and gloom. Being Austrian, Johanna mentioned feeling comforted in her grief by a musical called Elisabeth (pronounced e-lee-sa-bet), which I decided, trapped inside during a thunderstorm in lockdown, was worth checking out. Elisabeth isn’t an everyday musical, and centers around Elisabeth’s “love story” with Death, the manifestation of her depression that appears to lure her to take her own life, that’s best described by one of the show’s refrains: “Alle tanzen mit dem Tod, doch niemand wie Elisabeth” // “Everyone has danced with Death, but no one like Elizabeth”.

Death finds her at both her worst moments—the death of two of her children, when she discovers that her husband has been unfaithful, when the pressure at court begins to take its toll—but also at what should be the heights of her joy. Death isn’t always scary, either, which only makes him (I say “him” because that’s how he’s referred to in the show, but the character’s been played by men, women, and at least one non-binary person) more terrifying; he often sings softly, cajolingly, telling Elisabeth to just rest in his arms and let him “comfort” her, that “the shadows are growing longer,” that “It was evening before [her] day began”, that “[she’s] are only dragging [her family] into the night”.

Sometimes he sounds downright mesmerizing, and you almost fall for his words yourself. But Elisabeth never sings so softly back. Whenever she rejects him (as she does, over and over and over again), she screams and refuses, throwing up her arms and telling him to get out, that she is stronger on her own, and that she belongs only to herself.

Elisabeth’s mental decline parallels the political and social decline of the Austro-Hungarian empire around her, as everything that happens in the background of the musical drags it closer, kicking and screaming, to the eventual shooting of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in 1914, which will set off WWI. The public are starving and turn to radicalization and violence just to be able to live, and eventually they will turn into the Nazis that nearly killed a woman called Hannah, a German Jew who burst her eardrum by jumping off of a train headed to Auschwitz in 1944, who’s both my namesake and part of the reason I began studying German eighty years later, to learn more about my heritage.

But the question still remains: why do we choose to consume content that on the surface, is incredibly depressing and should make us feel even worse than we already do? Well, if you’ve ever heard Lana Del Rey’s song “Hope Is A Dangerous Thing For a Woman Like Me To Have (But I Have It)”, you’ll have probably guessed that it gave me the name for the article. It’s about depression as well; specifically, Sylvia Plath, a famous poet who took her own life, and whose story connected with Lana, who herself is diagnosed with depression.

Neither Elisabeth nor I have that exact diagnosis, but Elisabeth likely would today, and that knowledge does give me a little comfort when I take my Prozac in the morning with my bagel. Someone said to me once that when you are going through depression, two words are vital: “I understand.” And though I didn’t understand at the time they spoke to me, when I made the choice to listen to the musical, it felt like Elisabeth reached through the screen to me and said it to me: “Ich auch. Ich verstehe.” “Me too. I understand.”

We should remember that Elisabeth was born in 1837, and managed to live sixty years without giving in to the voices in her head. She suffered for it in a time when she couldn’t get any help. Elisabeth is a cautionary tale: we cannot allow ourselves to remain stuck in the past, to isolate ourselves in fear of change, to reject all the help we are offered. Elisabeth only discovered this too late, after she’d lost the people she loved most, but we don’t have to follow her path. We don’t have to go through this alone. There can be hope in the darkness. Because media about the darkness proves that we are not insane, that the darkness exists, that we are not weaker or more foolish for struggling.

After Elisabeth, I found other musicals in German, ones that range from questioning one’s very existence in Die Päpstin (“Wer bin ich, Gott, warum hast du mich gebor’n?” // “Who am I, God, why did you give me life?”), to the terror of never being enough in Mozart (“Wie wird man seinen Schatten los? Wie sagt man seinem Schicksal ‘Nein’?” // “How can you ever escape your shadow? How can you tell your destiny, ‘no’?”, to the many other moving stories of all-consuming grief in Rebecca, the cost of revenge in Artus: Excalibur, and abuse in Fruhlings Erwachen.

Every few months, whenever there’s a thunderstorm that rattles the foundation of my house and I don’t feel motivated enough to get out of the bubblegum pink papasan chair in my room, I relisten to them and see how much I can understand to check my progress in my German studies. Three years after the first time I couldn’t make myself get out of bed, they still say to me, “Ich auch. Ich verstehe.”

On one of those days, I decided to email the The Fresh Hell Podcast to give them an (abridged) version of this story, and Annie said in her response, after we spoke about true crime a little, “I’m so happy you feel included, as you should, but sad you also struggle with your health. It’s exhausting sometimes, huh?” At that moment, I felt it again: “Ich auch. Ich verstehe.” The Fresh Hell Podcast ends each episode by telling their viewers to be kind—to other people, to their pets, and most importantly, to themselves—and then a quote by Winston Churchill, “If you, yourself, are going through hell, keep going.”

Sometimes one thing leads to another. Sometimes a split-second decision you make can change your life. Perhaps you, like Elisabeth, Sylvia, Lana, Johanna, Annie, or I, sometimes find it hard to get out of bed. But we don’t have to be afraid of the dark. So, I’ll say what obscure German musicals, a strange little true crime podcast, and the songs of Lana Del Rey have said to me: “Ich auch.” “Ich verstehe.” “Me too.” “I understand.” “I’ve been there.” And most importantly, “you will survive.” And of course, dear reader, if you, yourself, are going through hell, please, keep going.