By Staff Editor, Lila Ackerman

On May 1, 2024, an encampment of SUNY New Paltz students protesting the war in Gaza began peacefully. Students created a community-like space, organizing workshops, setting up a library, and offering mutual aid services including food, mental health support, and know-your-rights training.

By the evening of May 2, however, the scene had drastically shifted. Police—including K-9 units, drones, and helicopters—swept in. Over 100 students were arrested, and witnesses described a violent crackdown: protestors dragged away, forcibly separated with batons, and in some cases, hospitalized.

But this article isn’t about the Israel-Palestine war, or the encampment itself. It’s about what came next.

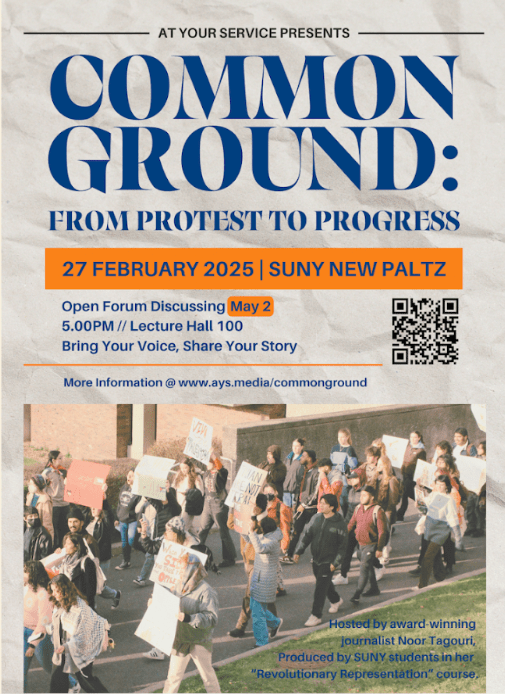

On February 27, 2025, nearly a year after the protest, an open forum event called “Common Ground: From Protest to Progress”, was held to reflect on the encampment’s aftermath. Hosted by Award winning journalist and Professor Noor Tagouri, along with students from her Revolutionary Representation class, the event aimed to create a space for reconciliation and freedom of expression—for people on all sides of the issue.

Even before it began, the event sparked tension. Shay Revenew, one of the student organizers, shared that she and others had received threats and criticism online.

“People thought we were monetizing off the event—which we weren’t,” she said. “Some were upset that it was being filmed, even though we designated a no-filming area.” Backlash prior to the event demonstrated the growing essential need for conversations like these. Why was an event like this important—and why was it also risky to attend? Could common ground truly be found? And if so, could it lead to real change?

Once people gathered in person, clear guidelines were established to ensure respectful dialogue. As Shay pointed out, if someone used a word that could be considered harmful or inappropriate, they were asked to define it. This was important because interpretations of words can vary widely. The event was also moderated by Tagouri to ensure everyone had a chance to speak. Tagouri framed the conversation as one where “your intention is not a point you want to make, but a change you want to see.”

While some unexpected—and difficult—topics surfaced during the event, what emerged was a range of other nuanced and complicated ideas that heightened the effect of this conversation, and the need for conversations like these.

“Your intention is not a point you want to make, but a change you want to see.”

Noor Tagouri

In today’s political and social climate, even the most straightforward topics often escalate into hostile debates. Productive, open-minded conversations are frequently overshadowed by emotions and feelings of superiority. This makes it difficult to have meaningful dialogues with people who hold opposing views. During this event, the topic of social media came up several times, especially in relation to meaningful conversation. Social media has the ability to amplify or distort opinions, particularly on controversial subjects like the Israel-Palestine war.

As one participant put it, “Social media, I believe, is real—it empowers people to speak out. But we have to use discernment. We need to change our relationship with it, which is why I believe in coming back together in person.”

Tagouri briefly mentioned the backlash she received on social media regarding the event. She shared her thoughts: “The event sparked controversy—disinformation, fear, and backlash—but that only affirmed its necessity.”

This is all to say, only 15 minutes into the discussion, some sort of common ground was found—the idea that change happens in person. Having to talk face-to-face with someone is very different than looking at someone through an iPhone screen. It provides you with a nuanced perspective, a deeper connection, and as Tagouri put it, “once we sit face-to-face, it’s harder to dehumanize one another.”

“Once we sit face-to-face, it’s harder to dehumanize one another.”

Noor Tagouri

The real reason that change happens in person though, is through storytelling. Storytelling was a powerful tool that emerged, and it unified people through empathy. One woman talked about how she visited the campus the day after the arrests, and it looked as though it had been “sanitized”—the sun was shining and the violence from the night before was absent. It was as if people had already moved on, disregarding everyone who had been impacted.

A former Rabbi had also attended the event, and mentioned having strong ties with Israel—his great uncle and aunt were Holocaust survivors, and moved to Israel after WWII. “I do not support the encampments,” he began, but continued by making it clear that he supports free speech and freedom to protest. However, he found it hard to endorse the encampments, especially after hearing some of the slogans used during the event, including “from the river to the sea.”

Once he mentioned that phrase, people shifted in their seats. There was a visible atmospheric change, and the Rabbi opened up conversations for people with differing opinions on this phrase. He described his personal association with it, and how he viewed it as the complete elimination of Israel or a denial of the Jewish people’s right to exist in the region. People listened respectfully, and then the microphone was passed to another woman who shared her belief on the phrase. “It represents a call for Palestinian self-determination, freedom, and an end to occupation,” she claimed, after describing her backstory—her family had been displaced and kicked out of Israel since 1948, implying a different kind of trauma she associated with the phrase.

Lastly, the microphone was handed to a college student sitting next to me, whose perspective was equally needed—she described her position as being “in between both sides” and indicated that, for her, the key issue is ensuring that both Palestinians and Jews have a safe haven where they are treated equally and with respect, both having the right to self-determination and protection.

Shay reflected on this last student’s unique viewpoint, stating “It was enlightening to hear her perspective, and it showed that common ground is possible even when people don’t fully agree with either side.”

It also brought up an interesting point—this student was an example of how we may not be as polarized as we think. We often share fundamental values, but fight in different ways. Tagouri mentioned a Vietnam War veteran’s own story—William Charles O’Neill. “I interviewed him for my podcast. He eloquently said something I’ve been thinking about because of this event: “I chose to fight in the army to protect the rights of anti-war protesters at home.” That dichotomy—being able to hold those two truths—he said: “We were fighting about the same things. We were on two sides of the same coin.”

We often share fundamental values, but fight in different ways.

Tagouri followed up with, “Do I have it in me to fight for the right of someone or hold an event I disagree with, or to say something I disagree with? Do we really have it in us?”

This event gave opportunity for speakers with differing ideas to have productive discussion, due to their unique perspectives and backgrounds. Possibly, they even found fragments of similarity. And it’s not merely that stories were articulated and compared. Through the process of storytelling, empathy was cultivated, and there was a deliberate attempt at modeling how all opinions could coexist in a more tolerant society.

Besides general common grounds established, there was an idea that was also widely agreed upon specifically regarding the encampments. In this case, it was the recognition that “the police response of the encampment wasn’t morally right, and that the students deserved an apology from SUNY,” said Shay. No matter which side one was on, everyone raised their hands when asked if they thought the police arrests were violent and inappropriate. This was especially important due to the fact that SUNY New Paltz didn’t get national coverage, unlike other schools in similar situations, even though they had one of the highest arrest rates. This recognition provided everyone involved with an opportunity to feel heard. This event showed the importance of in person dialogue. A recent study found that in the US, 74% of people communicate more digitally than in person; is it therefore a wonder that we’re so polarized? When looking someone in the eyes, it’s harder to see them as an enemy. This doesn’t mean everyone has to think the same– understanding the other side can lead to a state of coexistence, where unique views are accepted. We can build a world where disagreements don’t have to mean division.